Numb3rs 409: Graphic

In this episode, Charlie uses fractal dimension to detect forged comics. He argues that forgeries take longer to draw, causing ink to seep out

in a way that increases "wrinkliness", which can be measured by fractal dimension.

How appropriate, then, that the show features renowned travellers through the dimensions of time

(Christopher Lloyd,

Back to the Future)

and space (Wil Wheaton,

Star Trek.)

Let's take a closer look at fractal dimension. There are many ways of associating a number called a dimension to

a fractal object. Here let's focus on the Hausdorff dimension. The main idea is to generalize 1-dimensional

length, 2-dimensional area, and 3-dimensional volume to d dimensions, where d does not have to be an integer!

First, we must determine some properties this d-dimensional Hausdorff measure should have.

Felix Hausdorff (1868-1942), the mathematician who gave this measure of dimension, helped pioneer the mathematical

field of topology, which generalizes geometry.

In a geometric figure, we can talk about the distance between two points.

Hausdorff described a class of spaces where distance is replaced by a more nebulous concept of closeness, given by

the "neighborhoods" of points in the space.

Hausdorff's axiom, that distinct points have neighborhoods that don't overlap, resembles the situation in geometry

where distinct points have positive (nonzero) distance from each other, but is a less strict condition.

The modern definition allows topological spaces where even this condition need not hold.

How Goldilocks measures dimension

(1)A basic property of length, area, and volume is that it is additive. If we break a figure up into (reasonable)

separate pieces, then the length, area, or volume of the whole figure is equal to the result of adding the measures

of the pieces. It is reasonable to think our d-dimensional measure should satisfy this same property.

(2)If we multiply the sides of a rectangle by r, the area is multiplied by r2

(r*r). If we multiply the sides of a box by r, the volume is multiplied by

r3 (r*r*r). This reflects the fact that area is 2-dimensional, and volume

is 3-dimensional. So d-dimensional measure "should" satisfy the property that when a figure is scaled by

a factor of r, its d-dimensional measure is multiplied by rd.

Hausdorff proved that there is a consistent way of doing the above. Now we determine dimension the same way

Goldilocks chooses porridge. If we try to measure a filled-in rectangle with a 3-dimensional measure (volume),

we find that it is too small (0 volume) because it has no thickness. On the other hand, if we split the rectangle

into (infinitely many) horizontal line segments, we find that the length is too big (infinite). The area measure

is "just right", providing a finite positive measure.

For the fractal objects we will consider on this webpage, there will be precisely one number d≥0 where

the d-dimensional measure is positive, but not infinite. For e<d, the e-dimensional measure will be infinite.

For e>d, the e-dimensional measure will be 0.

Our task will be to find the Hausdorff dimension, the d that is "just right".

The Cantor Set

Start with the closed unit interval [0,1] on the number line.

Remove the middle third, but include the endpoints so that you now have 2 closed intervals each

of length one third.

Remove the middle thirds of each of these two intervals, to form 4 smaller intervals.

Continue this process indefinitely.

The points that are never removed at any step in this process form the Cantor Set.

What is its fractal dimension?

The key observation here is that the Cantor Set can be broken up into two pieces, the left side and right side,

which are scaled down versions of the Cantor Set itself! The scale factor is 1/3.

Let M_d(a figure) denote the d-dimensional measure of that figure.

By property (1) above, M_d(Cantor Set)=M_d(left piece)+M_d(right piece).

By property (2), M_d(left piece)=M_d(right piece)=M_d(Cantor Set) * (1/3)d

Putting these equations together, M_d(Cantor Set)=M_d(Cantor Set) * 2 * (1/3)d

If d is the Hausdorff dimension, then M_d(Cantor Set) is just right - a nonzero finite number. So we can

divide both sides of the equation by it to obtain:

1=2*(1/3)d, or in other words 3d=2.

In high school algebra, one learns that equations like this are solved via logarithms: d=log(2)/log(3).

Activity 1

Compute the Haudorff dimensions of the following fractals:

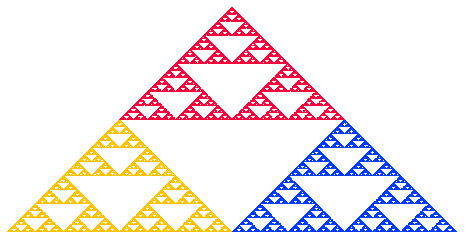

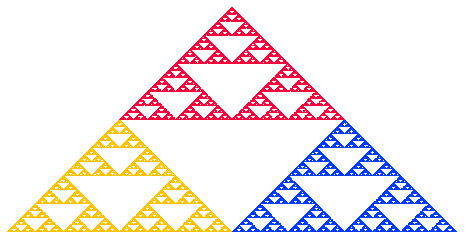

-

Sierpinksi triangle

Step 1) Start with an equilateral triangle. Divide it into 4 congruent subtriangles, and remove

the middle one, as in the Zelda Triforce.

| Power! Wisdom! Courage! |

Step 2) For each remaining triangle, perform a scaled down version of step 1.

Step 3) Repeat indefinitely.

The points never removed in this process form

Sierpinski's triangle.

Bonus: If you know Pascal's triangle, see if you can find a connection between it and Sierpinski's.

-

The Menger sponge

Start with a 3x3x3 cube and remove the center 1x1x1 cube, as well as the center 1x1x1 cube of each face.

Repeating this process as in the fractals we have seen above leads to the Menger sponge.

.jpg)

-

Koch curve

This is a piece of the more familiar Koch snowflake (which is obtained by arranging three of

these to form a "triangle".) Start with a closed unit interval [0,1]. Remove the middle third, as

when forming the Cantor set, but this time replace it with the other two sides of an equilateral

triangle that could be placed on top of this middle segment, as in the figure below.

Now, with the four segments of length 1/3, perform the same procedure. Repeating this process and taking

the "limit" yields the Koch curve.

Now, with the four segments of length 1/3, perform the same procedure. Repeating this process and taking

the "limit" yields the Koch curve.

-

Invent your own.

Come up with a rule to produce a fractal similar to the ones above.

Compute its Hausdorff dimension.

Check your answers:

Wikipedia provides a

list

of fractals by Hausdorff dimension.

How long is a pen stroke?

Benoît B.

Mandelbrot published a paper in 1967

in which he observed that the finer a scale one uses to measure a physical curve, the longer the curve seems to be.

It does not become close to being straight at larger degrees of magnification. He conjectured the apparent length

would be proportional to the measurement scale raised to the power of (Hausdorff dimension - 1). This would make

the apparent length of physical curves tend to infinity as we refine our measurements.

Activity 2

Estimate the Hausdorff dimension of a real-world curve, by measuring its length at several different scales.

Using your data, find the dimension that best fits Hausdorff's conjecture.

This could be something small, like a pen stroke, or something quite large. (If your curve is small,

you will need to use a microscope.) Try to find something you can break into pieces, so that a group of people

can cooperate in taking the length measurements for the smaller scales (i.e., the scales with greater precision).

Felix Hausdorff (1868-1942), the mathematician who gave this measure of dimension, helped pioneer the mathematical

field of topology, which generalizes geometry.

In a geometric figure, we can talk about the distance between two points.

Hausdorff described a class of spaces where distance is replaced by a more nebulous concept of closeness, given by

the "neighborhoods" of points in the space.

Hausdorff's axiom, that distinct points have neighborhoods that don't overlap, resembles the situation in geometry

where distinct points have positive (nonzero) distance from each other, but is a less strict condition.

The modern definition allows topological spaces where even this condition need not hold.

Felix Hausdorff (1868-1942), the mathematician who gave this measure of dimension, helped pioneer the mathematical

field of topology, which generalizes geometry.

In a geometric figure, we can talk about the distance between two points.

Hausdorff described a class of spaces where distance is replaced by a more nebulous concept of closeness, given by

the "neighborhoods" of points in the space.

Hausdorff's axiom, that distinct points have neighborhoods that don't overlap, resembles the situation in geometry

where distinct points have positive (nonzero) distance from each other, but is a less strict condition.

The modern definition allows topological spaces where even this condition need not hold.

.jpg)

Now, with the four segments of length 1/3, perform the same procedure. Repeating this process and taking

the "limit" yields the Koch curve.

Now, with the four segments of length 1/3, perform the same procedure. Repeating this process and taking

the "limit" yields the Koch curve.