After four people nearly die from poisoning, Don learns someone is tampering with nonprescription drugs. When the perpetrator publishes a manifesto in a local paper, Don is led to believe the person may be a former employee of the drug company that manufactured the drug.

In this episode, Charlie uses information theory and information entropy to help understand the manifesto and probabilistic graph theory in an attempt to determine where the perpetrator is likely to be found.

Charlie describes Information Theory as the branch of mathematics that formalizes the study of how to ``get a message from point A to point B'' and explains that this theory provides a good working definition of what the information content of a message is. As there are different ways to hear the same song for example, this definition should not depend on the form of the message.

A very common mistake is to believe that information theory is about what messages mean, that is to say to believe that content means here quality rather than quantity.

Indeed, tools like information entropy allow mathematicians to give meaning to and answer sentences like ``how much information is present in this message'', just like a scale tells you how much something weighs without saying anything about whether it's steel or wood, for example.

Suppose you were to ask someone you just met for them to tell you their address. From a mathematical point of view, this experience is similar to randomly picking an address out of the yellow pages, say. Indeed, while you can't tell a priori what the answer is going to be, different locations are more or less likely depending on the context - the languages they speak, for example, or whether they go to your college.

Another important concept in information theory is that of noise, which generalizes the intuitive definition of that word. For example, a very loud car passing by could make you misshear the person you're talking to and alter the message that you get, as electromagnetic interferences could modify the signal your cell phone is picking up.

We are thus led to model the process of ``getting a message from A to B'' as a random process. In other words, receiving a message becomes sampling a random variable.

Suppose now given a question X whose possible answers are x1,...,xn, and assume that the probabilty that the answer that you actually get be xi is pi. Thus by definition P(X = xi) = pi.

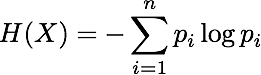

We would like to assign to this question X a numerial value - i.e. a number - H(X) called its entropy and measuring ``how much information you would get if you knew the answer to X''. How to define such a function is not obvious, at first sight. The following activity explores the first properties one would expect H(X) to satisfy if it indeed existed.

Now, suppose you have two questions X and Y, how much information is contained in knowing the answer to both X and Y? We know the information given by X is H(X) and that given by Y is H(Y), so you might be tempted to think the answer is H(X) + H(Y). Indeed, if you're given one pound of apples and one pound of oranges, you do have two pounds of fruits. One has to be more careful here, though. If X and Y are not inpendant (if X = Y for example) then the above additive formula can't hold. In other words, knowing one person's name and their name doesn't count as knowing two things about that person, obviously!!

Other mathematical considerations show that there is a function H that satisfies all these properties and whose definition is the following:

The following activity should help you convince yourself that this is a reasonable definition

The following activity is more challenging and involves calculating the entropy of a non-trivial random process:

Now that we have defined the entropy of a random variable and said that it measures the "information content" of a message, the only thing missing is a unit.

So what unit do we measure entropy in? From now on, we'll assume the logarithm in the definition of entropy is taken to be the base-2 logarithm log2, defined by log2(x) = log(x) / log(2).

Knowing whether a switch is on the on or off position is the most elementary piece of knowledge -- as is any answer to a yes or no question. It can be encoded with an alphabet of two caracters, 0 (for off) and 1 (for on) for example. We call such an information a bit.

We have seen that it takes n bits, that is to say n switches if you will, to encode the value of a message that can take 2n equally likely values. We have also seen that the entropy of such a message is exactly n.

On the other hand, if we already know the message, there is no need for any bits to encode the information, and the entropy is also 0.

This suggests that entropy might be a measure of how many bits are needed to encode the value of a message. Further investigations show that this is indeed true, as long as one considers this number of bits as a theoretical lower bound -- meaning you would need at least that many bits.

In other words, entropy measures the content of a message in bits

The following activity introduces the notion of data compression and shows how one can get closer to the theoretical bound provided by the entropy.

Suppose we are investigating sending a one character message that can take values amongst a, b, c or d with probabilities given in the following table:

| xi | a | b | c | d |

| pi | 2/3 | 4/27 | 4/27 | 1/27 |

| xi | a | b | c | d |

| Bits | 00 | 01 | 10 | 11 |

We want to encode the following sequences of messages: aaabaccbaa and abacaaaaaa. How many bits are needed to encode those sequences? What are the corresponding bit sequences?

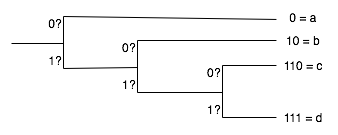

| xi | a | b | c | d |

| Bits | 0 | 10 | 110 | 111 |

What are now the bit sequences corresponding to our previous two sequences (aaabaccbaa and abacaaaa)? How many bits are actually used needed now? What is the average number of bits per message, that is to say per character? How does this relate to the entropy you calculated in question 1?

the following decision tree might help you amswer those questions.

So how does one go about constructing such trees? The example above is in fact a very example of what is called data compression and the idea used to construct the above table is based on the same kind of ideas the ZIP compression technique is. To learn more about this, you can read this.