Numb3rs 101: Pilot

In this episode, a serial murder-rapist has made numerous

attacks in the Los Angeles area. Making some seemingly harmless

basic assumptions, Charlie builds a statistical model of the attacker's

behavior which helps the FBI stop the murders.

What does practical mean?

A model of the attacker's behavior could be a number of different

things. Don and the FBI want to know where the next attack will

be. Charlie points out that this might be the incorrect approach

to the problem by making an analogy to a sprinkler. He proposes

that finding the sprinkler would be easier than deducing the location

of the next point where a drop will hit. In many ways, Charlie is

probably correct. We can probably assume that the killer has an

apartment where he or she spends quite a bit of time. If we can

find the most likely neighborhood where the attacker resides, it should

be easier on FBI resources than sending a dozen agents to patrol

several neighborhoods searching for an attack in progress. A

second reason, going back to the analogy of the sprinkler, is that the

physics of finding the next sprinkler drop are quite complicated; by

this, Charlie means that regardless of how many drops we've seen hit

the ground, the area where we should look for the next drop to hit will

be quite large. In the best possible model, more data should

provide significantly better deductions. Since the sprinkler is

stationary, however, the seeming randomness of the action of physics on

each droplet will affect Charlie's model less and less as the number of

droplets are observed.

We will define a model of the attacker's behavior to be a function

p(x) from the addresses in Los Angeles to the unit interval (the

interval [0,1]). That is to say that if x is a location in Los

Angeles, then p(x) is a number between 0 and 1. Not just any

function will do, however. We require the function p(x) to have

the following property: when we sum the values p(x) over all addresses,

the result is 1. We then call p(x) the probability that x is the

killer's address. Where p(x) is higher, the assailant is more

likely to reside.

After thinking about the problem briefly, we realize that we have

our hands full: there are infinitely many models to choose from.

We somehow need to find the right one. However, we don't even

have a concept of what right means. In laymen's terms, we need

the model to "fit the data." How do we quantify this common

notion so that we may make mathematical deductions? Charlie makes

a point that when a person tries to make a bunch of points on a plane

appear randomly distributed, the result is that the points adjacent to

any given point x are all approximately the same distance away from

x. Charlie uses this information to produce his model. As

one can see from the map Charlie brings to the FBI, the "hot spot" -

the most likely area where the perpetrator lives - which Charlie

computes is in what we might imagine is the "center" of the attacks.

Unfortunately, Charlie's model fails. The FBI gets DNA samples

from every resident of the neighborhood Charlie says they should check,

but none of the DNA matches the perpetrator's. So, Charlie has to

ask himself if the model he made was good. He sees one data point

which appears anomalous. However, any model with the properties

we outlined above shouldn't be affected too much by a single data

point. Indeed, after fixing the error, Charlie's new model has a

smaller hot zone which lies completely within the one the FBI already

checked. He is stunned by the realization that his model is bad.

Eventually, Charlie realizes that he has made a classic

error. It is sometimes quipped that the only difference between

physicists and engineers is that physicists can be sloppy in their

approximations. A physicist wanting to produce a set of laws of

physics which is as complete as possible will not choose the most

complicated set of laws before trying out a simpler set first. In

the same way, Charlie chooses the mathematically practical approach by

choosing the simplest possible solution to his problem by assuming

there would be exactly one hot zone. It is mathematically

practical in the sense that solving this complicated problem is a lot

easier with one hot zone than two. Generally this is a good way

to approach a problem; at worst one learns why the easy approach does

not work which hopefully gives some clues as to what the more

complicated approach should look like. With two hot zones (one

representing home and the other representing work), Charlie's model

gives more accurate results: one hot zone is in the same neighborhood

as before, the other is in an industrial area, and the hottest parts of

the hot zones are quite small. After making the arrest, Don

notices that the perpetrator had moved from the original hot zone a few

weeks ago, which is why the FBI hadn't found him in their original

search.

How did Charlie produce his model?

Of all the possible models, how did Charlie find that specific

one? Not many clues are given in the episode as to what method he

uses. So, let's consider the following more tractable

problem. Suppose we have done the following experiment: we hung a

spring from the ceiling and measured the lengths of the spring after

attaching a weight. After doing this for several different

weights, we have collected a bunch of data. After making a graph

of weight versus change in length, we might notice that the points form

almost a line (assuming the weights aren't too heavy). This means

that if the weight is W and the change in length is L, W=kL for some

number k (this relationship is called Hooke's law after the British

physicist born in the 1600s). How do we compute k? We could

draw in a bunch of lines which seem to approximate our data well and

pick the one which is the best. This is called the linear

regression problem. But which one is the best? There are

many different concepts of that, and the simplest one isn't the one we

generally use.

Let M denote the set of all lines through the origin. M is our

set of models. Let S denote the set of points which we have

computed experimentally. Given any line W(L) in the set M and

data point (x,y), compute the quantity  , the

vertical distance between the line W and the point (x,y). Add up

the quantities

, the

vertical distance between the line W and the point (x,y). Add up

the quantities  for each point in

S. This gives us a mapping from the set of models to the

non-negative real numbers. Generally, a map from a set of

functions (in this case, lines) to the real numbers is called a

functional. Denote our functional by A(W). If we can find a

line for which A(W) = 0, then our data points are all colinear.

This is generally not going to happen. The next best thing would

be to find a line W for which A(W) is as small as possible. In

this case, we say that such a line W minimizes A(W).

for each point in

S. This gives us a mapping from the set of models to the

non-negative real numbers. Generally, a map from a set of

functions (in this case, lines) to the real numbers is called a

functional. Denote our functional by A(W). If we can find a

line for which A(W) = 0, then our data points are all colinear.

This is generally not going to happen. The next best thing would

be to find a line W for which A(W) is as small as possible. In

this case, we say that such a line W minimizes A(W).

So now we must find a line which minimizes A(W). When one

wishes to minimize a quantity, one generally uses differential

calculus. Unfortunately, the absolute value function has no

derivative at zero. So, square the distance first! Instead

of adding up  to create A(W), we

add up

to create A(W), we

add up  . This is

called the method of least squares and is generally the accepted method

of solving the linear regression problem. To solve the problem

requires a little calculus. Wolfram's website has a relatively

good explanation.

. This is

called the method of least squares and is generally the accepted method

of solving the linear regression problem. To solve the problem

requires a little calculus. Wolfram's website has a relatively

good explanation.

Notice that there was nothing special about the line here. Any

set of functions M and non-negative functional A(W) would have worked

(although there will be technical problems if M and A are not chosen

wisely, such as not being able to find a minimizing function inside our

set M). So we could have found the quadratic polynomial of best

fit or the exponential of best fit in a similar fashion, although

solving such a problem will no doubt be vastly more complicated.

This method is a general approach used by mathematicians in a

variety of situations. The difficulty is generally in proving the

existence of a function which minimizes whichever functional we have

decided to work with. In physics, one often hears that objects

take the path of least action or least energy. That is to say

that rather than solving a very complicated differential equation, we

could solve a variational

problem instead. This method is so useful that it is basis of

theoretical physics.

Random sequences?

Charlie makes a comment that to

consciously construct a random sequence is impossible. This is

true in many ways. As an example, consider the following property

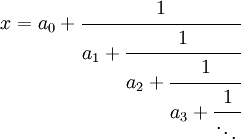

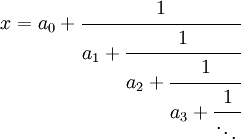

of sequences due to Khinchin. Given any real

number x we can find a continued

fraction expansion

In fact, as long as x is irrational, the

continued fraction expansion is unique.

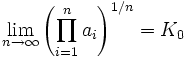

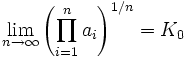

Khinchin's

Theorem says that

for almost every continued

fraction. Here

almost every

refers to a somewhat complicated notion from

measure theory.

Luckily, in our case it means exactly what it sounds like. What

is interesting is that no one has been able to demonstrate a continued

fraction which has the property given above. So, truly, we are

not very good at coming up with random sequences at all!

, the

vertical distance between the line W and the point (x,y). Add up

the quantities

, the

vertical distance between the line W and the point (x,y). Add up

the quantities  for each point in

S. This gives us a mapping from the set of models to the

non-negative real numbers. Generally, a map from a set of

functions (in this case, lines) to the real numbers is called a

functional. Denote our functional by A(W). If we can find a

line for which A(W) = 0, then our data points are all colinear.

This is generally not going to happen. The next best thing would

be to find a line W for which A(W) is as small as possible. In

this case, we say that such a line W minimizes A(W).

for each point in

S. This gives us a mapping from the set of models to the

non-negative real numbers. Generally, a map from a set of

functions (in this case, lines) to the real numbers is called a

functional. Denote our functional by A(W). If we can find a

line for which A(W) = 0, then our data points are all colinear.

This is generally not going to happen. The next best thing would

be to find a line W for which A(W) is as small as possible. In

this case, we say that such a line W minimizes A(W). . This is

called the method of least squares and is generally the accepted method

of solving the linear regression problem. To solve the problem

requires a little calculus. Wolfram's website has a

. This is

called the method of least squares and is generally the accepted method

of solving the linear regression problem. To solve the problem

requires a little calculus. Wolfram's website has a