Before jumping

in to some of the more mystifying applications of induction, let’s take

a look at how it works in some more straightforward (but by no means

trivial) examples. Consider the following claim:

The sum of the first n squares

is equal to (1/6)n(n + 1)(2n + 1).

Once again, this is easy enough to check by hand for the first few

values of n:

12

= 1 and (1/6)(1)(1 + 1)(2 x 1 + 1) = (1/6)(2)(3)

= 1,

yes;

12

+ 22 = 1 + 4 = 5 and

(1/6)(2)(2 + 1)(2 x 2 + 1)

= (1/6)(2)(3)(5) =

5,

yes;

12

+22 +32 = 1+4+9 = 14

and (1/6)(3)(3+1)(2 x 3+1)

= (1/6)(3)(4)(7) =

14,

yes. So the claim holds up to the sum of the first 3 squares, but

already things are starting to get cumbersome, and this method of

checking

by hand has no hope of yielding a proof for

all such sums. We

need to

find a better way to go about things.

We might try the same method here

as was used in proving that all squares of even numbers are divisible

by four. Let n be any number, and consider the sum of the first n

squares:

12

+ 22 + 32 + 42

+ ... + (n − 1)2 + n2 .

If we could

somehow add up this sum and show that the result is (1/6)n(n + 1)(2n +

1) then we would be done. Problematically, there is no obvious way to

do this addition (try it and see). We turn to induction.

First comes

the base case n = 1: we must prove that the sum of the first 1 squares

is equal to (1/6)(1)(1 + 1)(2 x 1 + 1). This has already been done,

above, and it was rather easy; it is often true that the base case of

an inductive argument is easy or trivial.

Next comes the inductive

step. We start by making our inductive hypothesis: assume that the

claim is true for n. Our task is to show that it is also true for n +

1. In other words, we need to show that the sum of the first n + 1

squares is equal to

(1/6)(n +

1)[(n + 1) + 1][2(n + 1) + 1],

(1)

which

is just the original formula with n replaced everywhere by (n + 1).

Our

inductive hypothesis amounts to the following equation:

12

+ 22 + ...

+ (n − 1)2 + n2 =

(1/6)n(n + 1)(2n + 1).

Adding (n + 1)

2 to both sides

of the above equation yields

12

+ 22 + ... + (n − 1)2 +

n2 + (n +

1)2 = (1/6)n(n + 1)(2n + 1) + (n + 1)2.

Notice that the left hand side

of this equation is exactly the sum of the first (n + 1) squares! If we

could show that the right hand side of this equation is equal to the

formula labeled by (1), above, then we will have completed the

induction step. Although it is not immediately apparent, the two

formulas in question are in fact equal. The right sequence of algebraic

manipulations reveals this to be so:

(1/6)n(n +

1)(2n + 1) + (n + 1)2 =

(n + 1)[(1/6)n(2n + 1) + (n + 1)]

= (n + 1)[(1/3)n2

+ (7/6)n + 1]

= (n

+ 1) [(1/6)n + (1/3)][2n + 3]

= (1/6)(n + 1)(n + 2)(2n + 3).

Exercise 2

Verify the above equalities.

The reader is invited to verify these

calculations in more detail. Whatever detail is omitted here is done so

for the sake of clarity: there are only so many lines of algebra one

can reasonably be expected to read through before going cross-eyed. The

best path to understanding is to work out the details for your-self,

using the above as a guide.

This completes the induction and therefore

finishes the proof: we have verified that the sum of the first n

squares is always equal to (1/6)n(n + 1)(2n + 1). It is worth noting,

however, that I have left the origins of this formula a complete

mystery. Induction proved quite useful in verifying that the given

formula is the correct one, but how one might come to suspect that

formula in the first place is another issue entirely. I refer the

reader to [1], chapter 2, for a very pleasing exploration of this issue

(the rest of the book is nice, too).

Next I want to give an example of

induction used in a very different situation: to solve a puzzle which

at first glance doesn’t seem to have much use for induction at all. The

puzzle is a tiling puzzle. It asks:

Can a chessboard minus a rook’s

square be tiled with triominos?

What? The first step to solving any problem is understanding the

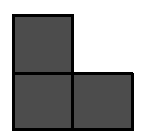

question, so we start with that. First, a ‘triomino’ is a

two-dimensional figure made out of three equal squares glued together

in the configuration pictured in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A triomino

A ‘chessboard’ is a more familiar object: it is an 8 x 8 square made

by gluing together 64 smaller squares. Implicit in the question is the

assumption that the squares that make up a triomino are the same size

as the squares that make up the chessboard. A ‘rook’s square’ is any

one of the four corner squares on the chessboard. Finally, the ‘tiling’

that the question asks for is an arrangement of triominos on the

chessboard such that every square of the chessboard (except for one

corner square) is covered by a square from a triomino. No two triominos

are allowed to overlap, and every triomino must be positioned so that

it lies entirely over the chessboard. Can this be done?

The answer is

yes, and if you can get your hands on some triominos (or make some

yourself), after a little experimentation you’ll be convinced of this.

So we can ask a harder question:

Can every 2n x 2n board, minus

a corner square, be tiled by triominos?

The chess board example corresponds to the case n = 3. We can proceed

in the general case by induction in a rather surprising way. That

induction is useful here is perhaps not so surprising, given the nature

of the claim we wish to prove (i.e. we want to prove the claim for n =

1, 2, 3, . . .). But the geometrical aspect of this problem contrasts

sharply with the previous example.

The base case for the induction is n

= 1, so we must consider a 2

1 x 2

1

board with one of the corner pieces

removed and determine whether this can be tiled by triominos. But of

course it can be, since what remains of the board is precisely the same

shape as a single triomino. Once again, the base case was easy.

Now the

induction step. We assume the result is true for n and try to prove it

true for n + 1. This means that we can assume that the 2

n x 2

n board,

with one corner piece removed, can be tiled by triominos. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: A tiling of the 2

n x 2

n

board, minus the upper right corner square.

Note that the actual tiling pattern is not shown; at this point we need

not be concerned with

how

the tiles are arranged, but merely that the

board minus the corner is tiled in

some

way.

How can we use this

tiling, our inductive hypothesis, to obtain the analogous result for a

2

n+1 x 2

n+1 board? Before

reading ahead to the solution, try to play

around with the possibilities for a time. The answer is not complicated

or difficult to understand, but it requires the right flashes of

insight to come up with it.

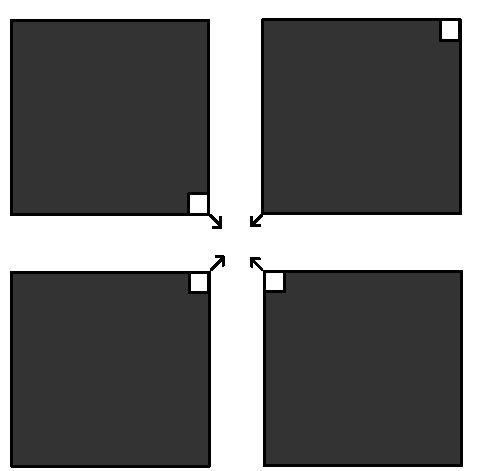

The first important insight is that the

2

n+1 x 2

n+1 board can be

divided into exactly four 2

n x 2

n

boards by

cutting it vertically and horizontally down the center lines. Our

inductive hypothesis tells us that we know how to tile such boards with

triominos, minus a corner square. So let that be done.

The second

insight is best provided in picture form: we glue the four quarters

back together in the configuration shown in Figure 3. This leaves one

corner square (the one in the upper right) untiled, along with three

central squares. But look! The three central squares that are untiled

have been glued back together in exactly the shape of a triomino!

Therefore, with the addition of one extra triomino in that conspicuous

space, we have managed to completely tile the 2

n+1 x 2

n+1 board, minus

the square in the upper right corner. This completes the induction and

finishes the proof.

Before moving on, it is worth noting a small

corollary to the result we just proved. Since each triomino is composed

of exactly three squares, any area that can be tiled with triominos

must consist of exactly 3k squares, where k is the number of triominos

used in the tiling.

Exercise 3

Show that the converse of this statement

is false. That is, show that there are areas consisting 3k squares, for

some natural number k, that cannot be tiled with triominos.

Figure 3: Gluing the four quarters back together.

The number

of squares in a 2

n x 2

n

board is 2

n x 2

n = 2

2n

. So a tiling of this

board minus a corner square is a tiling of an area consisting of

exactly 2

2n − 1 squares. We can therefore deduce

that 2

2n − 1 = 3k

n for

some k

n (the subscript n is included to indicate

that the number k

n

depends on n). This isn’t the most interesting result in the world, but

it is not exactly obvious and we get it for free from our tiling proof.

Exercise 4

Prove this result directly. That is, prove by induction on n without

reference to tilings that for all natural numbers n the number

22n − 1 is divisible by 3.

Exercise 5

Find an explicit formula for kn in terms of n.

(Hint: use the tiling proof or your answer to the

previous exercise to guess the formula and then verify it.)